Nemotode, Free-Swimming Ciliates & Flagellates

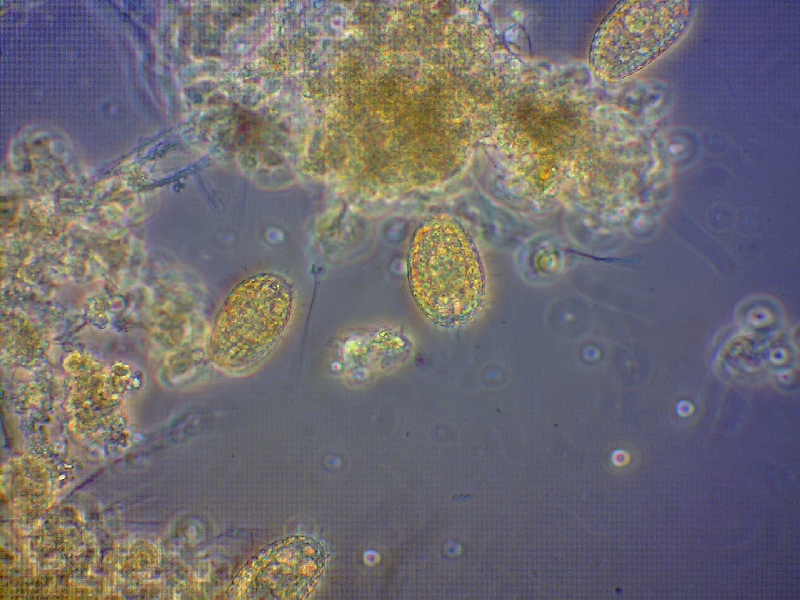

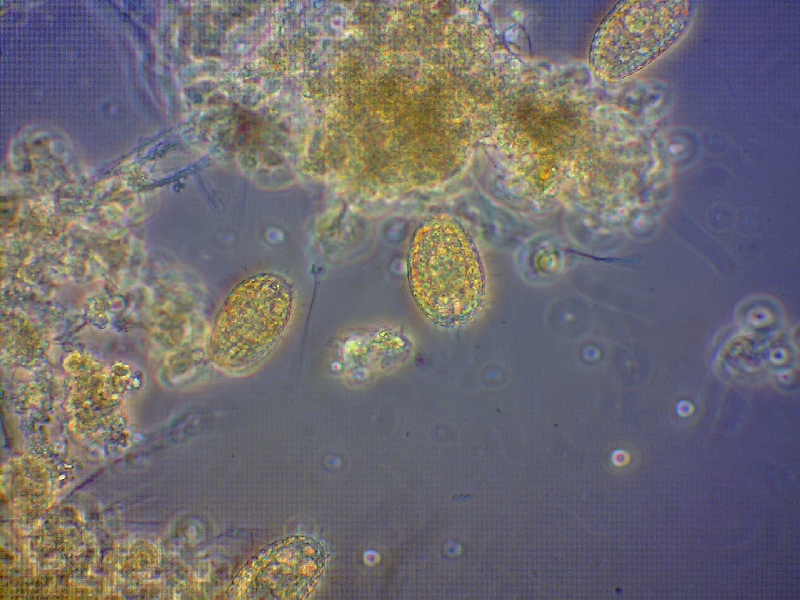

Flagellates belong to the class Mastigophora and range in size from 5-20 micrometers in diameter. They are commonly ovoid or pear-shaped with one to four flagella, hair-like projections used for locomotion, attached to one or both ends of the cell. The flagella can usually be observed at 1000X magnification. Some flagellates may form colonies in which the cell bodies are clumped together with their flagella projecting outward. Some flagellates contain chlorophyll and are capable of photosynthesis. Due to the particular characteristic of resembling plants they are often classified as flagellated algae rather than protozoa.

The locomotion of flagellates is usually fast and they seem to flip and twist as the flagella are “whipped” around to propel them. Some flagellates have multiple flagella. This makes them appear “bouncy” and unorganized due to their locomotion mechanism while other higher life forms such as free-swimming ciliates present a more organized locomotion mechanism. This is sometimes helpful in identifying flagellates under the microscope. When counting flagellates under the microscope, a 400X magnification should be used in order to identify them better due to their small size.

Flagellates feed on soluble organic matter and dispersed bacteria. Flagellates are more common in heavily loaded plants or during startups. They predominate when there is a high dispersed (single-celled) bacteria population density. They are sometimes associated with turbid effluents produced during toxic upsets. They also bloom when septic sludge or inadequate aeration causes anaerobic conditions in the aeration basin. Their presence in a wastewater treatment system indicates high soluble biochemical demand levels, low dissolved oxygen and high organic load. Typically higher life forms disappear when a chemical upset goes through a wastewater system. Flagellates are the first higher life form to come back after a chemical upset in the wastewater system. Flagellates can indicate when the wastewater system is getting healthier or if it is still overcoming a chemical upset.

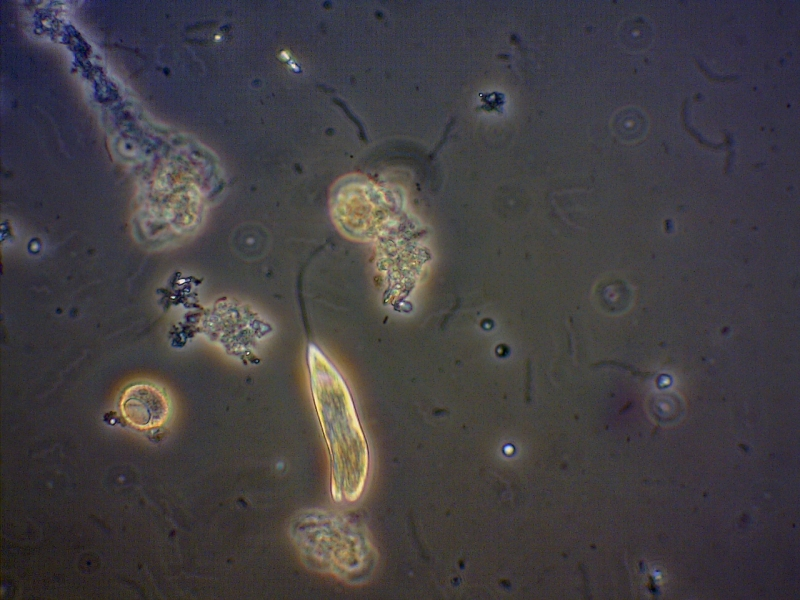

Nematode Photos

Nematodes are common and widespread metazoa. Most are 2-3 mm long and have a long thin shape and a slightly blunt anterior end, resembling earthworms. They are rather stiff and can move either by writhing or gliding through a substrate. At high magnification, a strong muscular pharynx is apparent near the front and egg-bearing ovaries near the back end. Nematodes occur in lightly loaded plants operated at a low F/M (food to mass) ratio. They are commonly found in old activated sludge with ample dissolved oxygen and in biofilm reactors. They can be used as a type of bioindicator for determining when toxins have been introduced into a system. Their burrowing action promotes floc health by allowing oxygen to penetrate the larger pieces of floc.

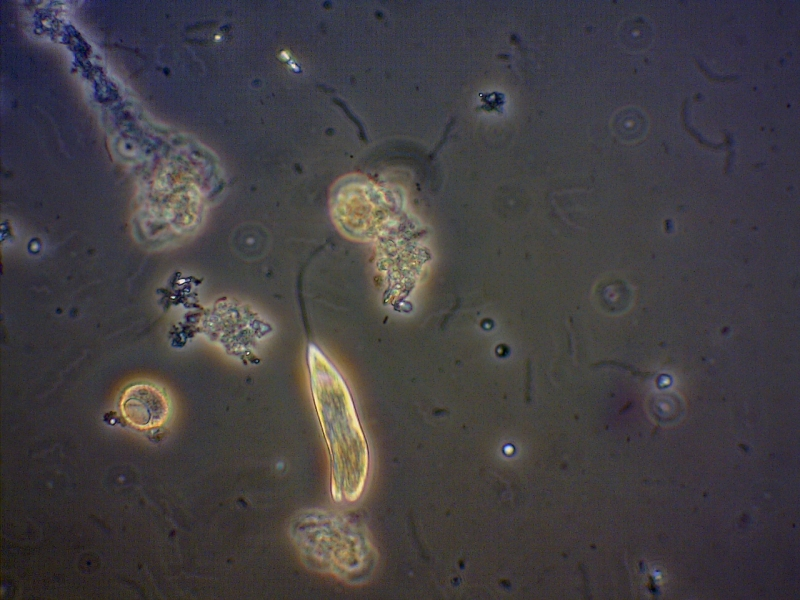

The ciliates are so named because of the cilia, small hairs that are distributed over the entire body. Ciliates are generally ovoid or pear-shaped and maintain their shape by means of a tough but flexible pellicle. Cilia protrude through the pellicle in a variety of patterns. The term ciliate comes from the Latin word “ciliate” which means eyelash.

Free-swimming ciliates range in size from 40-100 micrometers. Rapid, rhythmic cilia movement propels them through the liquid. Some are completely covered with cilia while others have cilia in rows or spirals around the cell. Euplotes, Colpidium, and Paramecium are common examples of free-swimming ciliates.

Some ciliates have specialized cilia that look and function like legs, allowing them to crawl around on floc particles and “flick” up the bacteria so that they can consume them. These are called crawling ciliates and tend to stay on the floc more than free in the bulk water. Aspidisca is one example of a crawling ciliate. The main purposes of their cilia are to propel the organisms and to gather food into their mouths (cytostome). They feed mostly on bacteria and other single cell organisms. They are sometimes identified by their smooth gliding or “swimming” motion through a sample or by the “crawling” movements around a piece of floc.

Ciliates are typical colonizers of biological sludge. Under optimum conditions, their numbers range from 1,000 to100,000 cells/mL. A sudden reduction in the number of individuals, or occurrence of encysted, inflated or dead ciliates, is an indication of shock loading with toxic substances or organic overloading. Therefore they are indicators of toxicity in wastewater systems such as ASB’s or Activated Sludge. Since they move fast and they prey on bacteria, ciliates helps to produce a low TSS and turbidity effluent. Some plants use the presence of ciliates to predict the quality of the plant’s effluent.